Update: 07/31/2014

Sonatype has reacted to this post and will soon be turning on SSL access for all users. Their blog post announcing this is here. I’m very happy that they are making this change, and the Java ecosystem is going to be more secure for it!

That being said, if you’re reading this and are thinking of charging $10 to gauge the true demand for security features in your product, don’t. Imagine if car companies decided to charge $10 to gauge the true demand for air bags. Luckily, we live in a world where car companies can’t legally do that.

I’m happy that Sonatype made this change in their policy, and I hope they continue to decrease friction for security features in their products. It’s our responsibility as developers to make the most secure product we can for our users. How much friction they are willing to endure for a security feature shouldn’t factor into it.

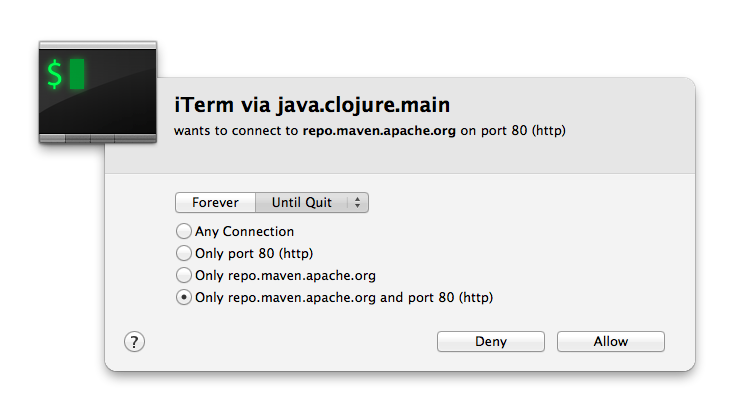

The other day I started hacking on a Clojure project of mine, when I saw my firewall display this:

I’m downloading clojure.jar from http//repo.maven.apache.org over port 80! This means that I’m going to be downloading JARs over unencrypted http. I thought this was an issue with leiningen at first. As it turns out it’s not lein’s fault at all. Clojure.jar, and a whole lot of other JARs that are important in the Java/Clojure/Scala/etc world are officially hosted on Maven Central, which is a public service provided by Sonatype. Sonatype has a policy that they only allow SSL access to people who have authentication tokens. In order to get an authentication token and SSL access, you need to donate $10 to the Apache foundation. If you don’t believe me, the donate page is here, and the blog post announcing this policy is here. They even mention man-in-the-middle attacks on it.

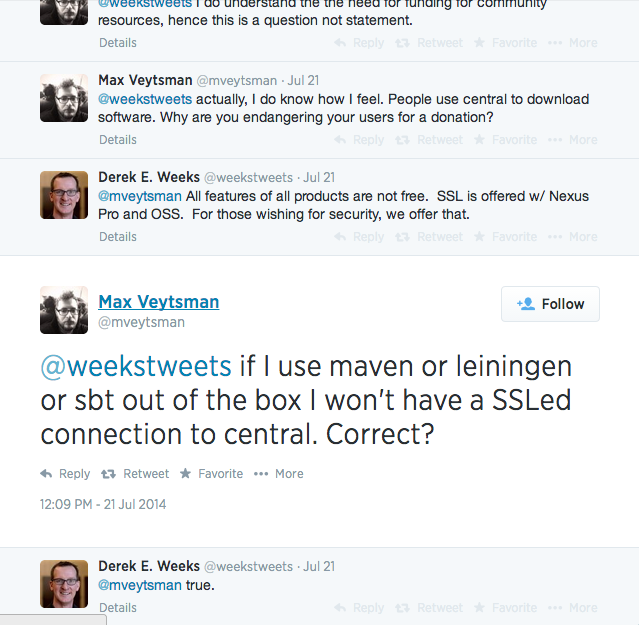

Because authentication tokens are issued per user/organization, tools like maven and leiningen can’t bundle authentication tokens. If you’re pulling down some Java project and installing its dependencies, you’re not going over SSL. This policy was confirmed by a Sonatype employee when I got into a twitter tiff about this:

Unless you take very careful steps that involve paying someone $10, JARs you download can be man-in-the-middled, and code you execute on your system can be replaced by malware.

When can this happen? If you ever use a public wifi network in a coffee shop, or are on a wifi network that someone took over you can be man-in-the-middled. Your ISP can man-in-the-middle you at will, and some do so in order to serve you ads. Or, perhaps you are subject to a man-in-the-middle attack from a state actor.

Dilettante

To prove how easy this is to do, I wrote dilettante, a man-in-the-middle proxy that intercepts JARs from maven central and injects malicious code into them.

Proxying HTTP traffic through dilettante will backdoor any JARs downloaded from maven central. The backdoored version will retain their functionality, but display a nice message to the user when they use the library. You can see the video below:

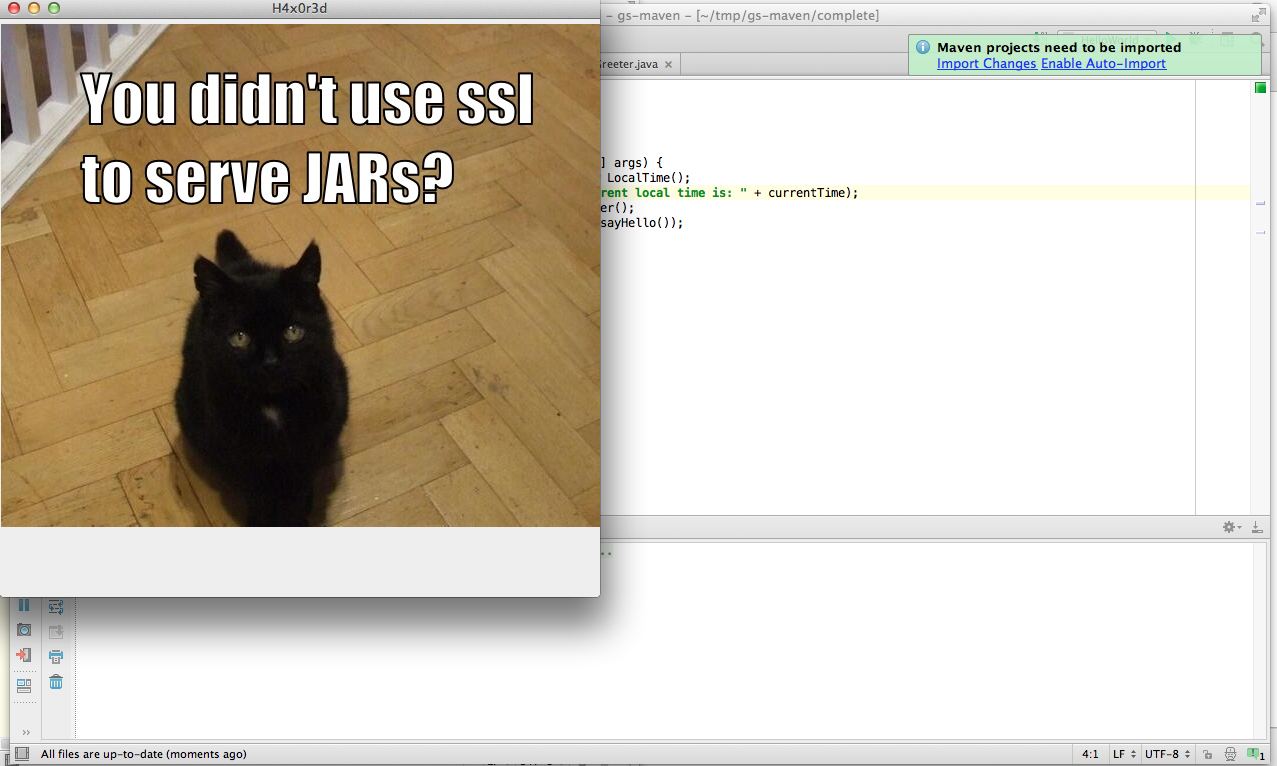

Or a screenshot:

You can find the code here

The Technical Details

When JARs are downloaded from Maven Central, they go over HTTP, so a man in the middle proxy can replace them at will. It’s possible to sign jars, but in my experimentation with standard tools, these signatures aren’t checked. The only other verification is a SHA1 sum, which is also sent over HTTP. When dilettante sees a JAR coming from Maven Central it replaces the original JAR with a backdoored version that runs malicious code on the victim’s computer. Since the SHA1 hashes are sent over HTTP only, dilettante simply replaces any hashes it sees with the hash of the corresponding backdoored JAR.

I used the excellent mitmproxy library to build my tool. I started by writing an inline script for the proxy and then moved on to creating a standalone tool with libmproxy.

A JAR is just a zip file that contains Java Class files, resources and some metadata. To backdoor a JAR, I can insert my own class by adding it to the zip archive:

package dilettante;

public class Dilettante {

public static void() {

// do some evil stuff

}

}

The trick is finding a way to call my malicious class. I know that my victim will be downloading some library, and I need to run my malicious code regardless of what classes in the library they actually use. I would also like to actual functionality of the library to not be affected.

Java has the concept of static class blocks, which are class level initializers — that is, they contain code that is run once when the class (not an instance!) is loaded into memory. After I insert a malicious class file into the jar, I can call it in a static block like this:

import dilettante.*;

static {

Dilettante.backdoor();

}

In order to inject the above snippet, I need to inject it into Java classes directly, not source files. I use Krakatau, a Java disassembler/assembler library for Python. It let’s me add the snippet in Jasmin format:

.method static <clinit> : ()V

; method code size: 4 bytes

.limit stack 0

.limit locals 0

invokestatic dilettante/Dilettante backdoor ()V

return

.end method

Limitations

This is a proof of concept!, and so it still has some limitations

Currently it’s not very fast. There are a couple of reasons for this

- I have to run a disassemble and an assemble step. It would be more efficient to directly append the assembled shim to the .class file.

- The way I am using Python’s zipfile library, I’m actually creating a second copy of every class in the zip. This is inefficient in terms of space and speed. Careful reading of the zip spec may lead to an efficient way of appending data to files inside a zip.

If a user is downloading multiple JARs in one go, we will backdoor each one. The malicious payload is executed only once per JAR, but if multiple JARs are backdoored, we will execute it several times. This issue will disappear if we replace the cat picture with a high quality persistent backdoor that is smart enough to only infect a system once :).